From Spits to Pennies

Money is an everyday part of our modern lives. Today, all it takes is a swipe of a magnetic card and a complete transaction is, zip, done. Even the use of paper money, a revolutionary innovation at its inception, is slowly being absorbed by the convenience of electronic banking. Without computer technology, the exchange of money was much different. Money has long history of creation, change, and innovation – credit and debit cards are just the latest addition. The ancient Greeks and their eastern neighbors fundamentally invented money as we know it today.

The first coins were invented in western Asia Minor in the seventh century BCE. This is not to say, however, that these were the first forms of money. Trade and barter of goods and services and even the trade of un-standardized metal, like pieces of jewelry, were common for millennia. The Mesopotamians and Egyptians, as early as the third millennium BCE, were using weighted pieces of metal called bullion as money. The evolution of bullion to coin is a long and somewhat fortuitous one, the start of which was in Greece and Asia.

In Greece, the systems of money during the eleventh to eighth centuries BCE were centered on trade, not the value of silver or gold. We find in Greek epic, like the stories written by Homer, that money was a system of value based on what an ox was worth. In the Iliad (23.885, 703, 705; 6.236) a bronze cauldron (lebes) is valued at one ox, a fine tripod is described as a “twelve-ox” tripod, a skilled female slave as a “four-ox” woman, and a set of bronze armor is worth nine oxen, compared with gold armor worth one hundred oxen. In the Odyssey (1.431) it is said that Odysseus’ father paid a price of twenty oxen “with his own possessions” for his household servant Euryclea.

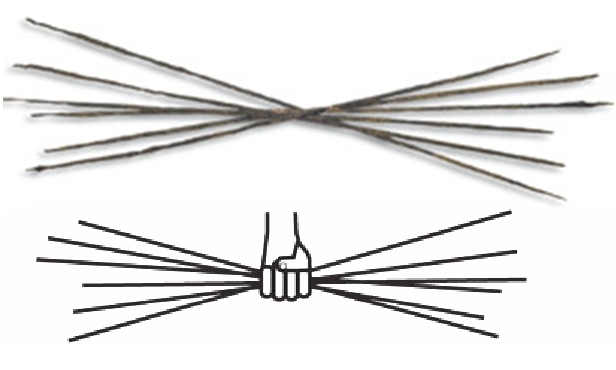

Interestingly, iron spits (obelos), six of which made up a “handful” (drax or drachme), also had monetary significance. They were used to roast meat but they were also used as objects for dedication to gods and unit measures of value. Over time, trade and money in the form of metal pieces became the most common way to transfer funds. People would simply cut up large pieces of gold, silver or jewelry for smaller, exact amounts.

This system however, did not prove to be the most convenient way to pay for goods. Each piece had to be weighed and even “standard” cut pieces had to be checked for quality and weight. (Any “standard” cut pieces of this time were minted by individuals themselves, so the only way to verify their worth was by weighing and checking the quality of metal, just as with every other purchase). While it may have worked well for large sums of money, making purchases and receiving money for many small transactions must have become incredibly cumbersome for both buyer and seller. How could people make buying and selling easier for everyone involved? The answer was found in a rather unexpected place and through rather unprecedented means.

The earliest coins were made of electrum, a gold and silver alloy naturally occurring in Lydian stream beds (located in modern-day Turkey). This alloy, readily available in the area, was used as currency. The electrum, however, was very hard to value since the amount of gold in each piece could vary greatly. No other cities would accept Lydian electrum as payment. To combat this problem, seventh century BCE authorities in the area decided to issue small, standardized and stamped pieces of electrum that would be verified in worth by the state. This introduction of state-issued, standardized coin became one of the largest and most influential happenings in monetary history.

Electrum, even when verified by the state, was too easily overvalued by lowering the amount of gold in each piece; so, with the invention of gold refining techniques in the sixth century BCE, electrum was phased out of circulation and replaced with pure gold, silver and eventually copper. Even so, the obvious benefits of state-issued coin, which was verified in weight and standardized by a trusted local government, were not lost on the ancient world. It was always guaranteed and did not need to be double-checked; this was the first kind of exchange that could be accepted "on trust."

The spread of government issued coin as a monetary system quickly swept across the Greek world. There were, however, a few places that rejected the use of coinage, most notably the polis of Sparta, which prohibited the use of coins until the third century BCE. The very earliest Lydian coins started the long held tradition of coins bearing an image that was connected with the land they came from. Cities of the ancient world could have their own symbols and deities in engravings; a portable, visible reminder of a particular place. These works of art became more and more intricate and detailed with increased spread and use.

Remember our spits from above? Their names are reflected in the standard denominations of ancient Greek coins: basic units were referred to as a stater (στατήρ), a drachma (δραχμή), and an obol (ὀβολός). Six obols made one drachma, and two drachmas made one stater.

Even with this success, there was one small problem yet to be resolved in the use of standardized coinage: how to make small change. Coins were first only minted in gold and silver, and by the sixth century BCE, silver was the dominant metal. It was more plentiful, more convenient and flexible, and good for low value exchange; but, if you wanted to buy something quite cheap, you would have to break a silver coin into pieces, or revert to trading in unstandardized lumps. This might be odd to the mind of a modern consumer since it seems silly to be able to buy a sheep with coins but not a cabbage. Smaller denominations of coins, made of bronze, started in the fifth century BCE, apparently in Sicily, where an onkia was valued at 1/60 of a drachma. It was not until the fourth century BCE that bronze coinage was readily found in the greater Greek world, including Athens. Bronze solved the problem of low-value transactions and solidified the use of coinage as the primary system of exchange for thousands of years.

That quarter in your pocket has long lineage of forebears that significantly influenced its design and functionality. Though much more complicated than a coin worth its weight in silver, our current monetary system still relies on the basic principles discovered by the Greeks and the Lydians almost 2,500 years ago. Standardized and guaranteed by the government, that quarter allows you to buy a single gumball without bringing round your sheep for trade.

References:

Kroll, John H. “The Monetary Background of Early Coinage.” The Oxford Handbook of Greek and Roman Coinage, ed. William E. Metcalf (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), pp. 33-42.

Jenkins, G.K. Ancient Greek Coins (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1972), pp. 9-25.

Carradice, Ian “Early Coinage and the Ancient Greek World.” Greek Coins (Austin: University of Texas Press 1995), pp. 19-30.