Coins and Art

Art in the Greek and Roman world went through many changes. Artists, developing their concept of proportion, style and detail, changed from rigid and stiff to more soft and fluid. The typical "archaic smile" became an expressive face of anguish and almond eyes changed from large and stylized to realistic and striking.

This is an example of archaic Greek art. This statue shows a transitional period from archaic to Classical as the mouth is a more "solemn pout" than the typical "archaic smile." The male nude is also more naturalistically shaped and smooth, another characteristic of early Classical sculpture. His rigid stance and long braided hair, however, are all features of archaic art.

Coins in the ancient world followed suit. Evolving from simple designs with few details to incredibly rich portraits and intricate carvings, coins represent some of the most interesting and far reaching art of the ancient world. The small scale of these coins only makes their work more impressive.

This coin is one of the oldest in Hallie Ford's collection. It is an example of one of the very first silver coins from Lydia, around 560-546 BCE. As one of the original experiments in using art on coins, its design is understandably rudimentary: showing a lion and boar head to head in battle, with an incuse mark on the reverse.

Archaic Period

Archaic coins, ca. 680-480 BCE, consisted of rough obverse image and (usually) no reverse design. Instead, there was a punch mark, also called an incuse mark; made when the mallet came down on the punch to push the metal into the obverse die. These could be random/irregular shapes, squares, double squares, or several divided triangles arranged in an artistic manner -- a sort of precursor to reverse illustration.

Transitional Period

The transitional period from Archaic to a more "Classical" style (480-415 BCE) produced many fine coins that exhibited a greater understanding of form and movement. It also saw the standardization of a reverse design that let artists and cities expand and enhance the iconography representative of their city. The Athenian "owl" design, with Athena on the obverse and an owl on the reverse, symbols of military strength and wisdom, became so synonymous with the city of Athens that the design changed only slightly for hundreds of years.

This particular Athenian coin features both Archaic and Classical elements. Athena's eyes are almond shaped and she has an "Archaic smile," but the style has developed from the very first Athenian owls. ΑΘE, a-th-e, (alpha, theta, epsilon) stands for Athens. Athens minted some of the first coins to have a reverse image.

Classical Period

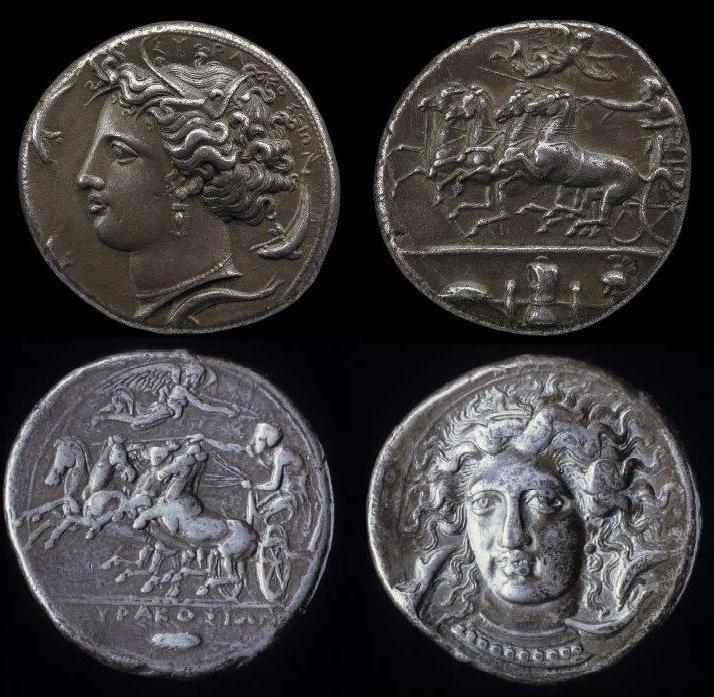

The Classical period, ca. 415 BCE-330 BCE, boasts some of the most beautiful and intricate designs ever seen on coinage, ancient or modern. Some are by great masters: for example, Kimon engraved a die with a beautiful portrait of Arethusa around 415-405 BCE and Euainetos carved a similar coin featuring Persephone. The size and proportion of the coin, in comparison to the details featured, were taken more into consideration. Aspects like hair, feathers, and folds of cloth were carved with great detail.

Hellenistic Period

Starting around 330 BCE, in conjunction with the expansion of Alexander the Great's kingdom, the world saw the rise of the Hellenistic age. This period experienced an increase in warfare that led to, inevitably, the decrease in quality of art. Coins were more hurriedly produced and, as safety became more pressing, inspiration and artistic appeal yielded to the necessity for fast coinage. Over time, a portrait of the nation's leader became expected rather than an exception.

Alexander the Great was in large part to thank for, not only the rise of the Hellenistic age, but also the acclimation to self-portraits on coins. The idealized Herakles that featured prominently on his coinage is said to be styled in the image of Alexander the Great. Whether this was true, we may never know; but, after his death, his successors were quick to first use Alexander's image and then their own on issued coinage. Dynastic portraiture quickly becomes the norm throughout the Greek world.

Roman coins followed a bit of a different path. Featuring mostly gods and goddesses from the very beginning of Roman coinage, it was not until first century BCE that the idea of self-portraiture was even attempted.

See this page for more discussion on the progression of Roman coinage.

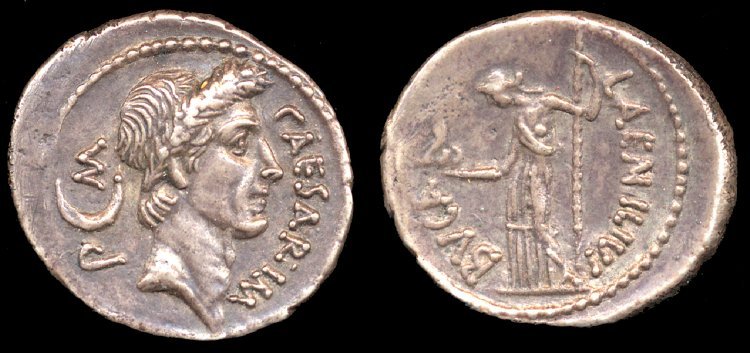

Julius Caesar, almost three hundred years after Alexander the Great, was the first living individual to be featured on a Roman coin. Coins bearing his image were first minted in early 44 BCE; his assassination happened only a few months later. This motif created a precedent that every Roman emperor after him followed - a portrait on the OBVERSE and a reference to imperial power or piety on the REVERSE (following the example set by the Hellenistic monarchs hundreds of years before).

This coin, minted by L. Aemilius Buca in 44 BCE, under Julius Caesar, is one of the first coins to bear the image of a living Roman. While Caesar released many of his own coins, it is important to note that it is only under Caesar's four appointed moneyers (called quattuorviri monetales) that his image is used. Caesar's own strikings focus on Venus Genetrix (his ancestor) and his military victories.

Check out this site for more information about the coinage of Julius Caesar.

Imperial Period

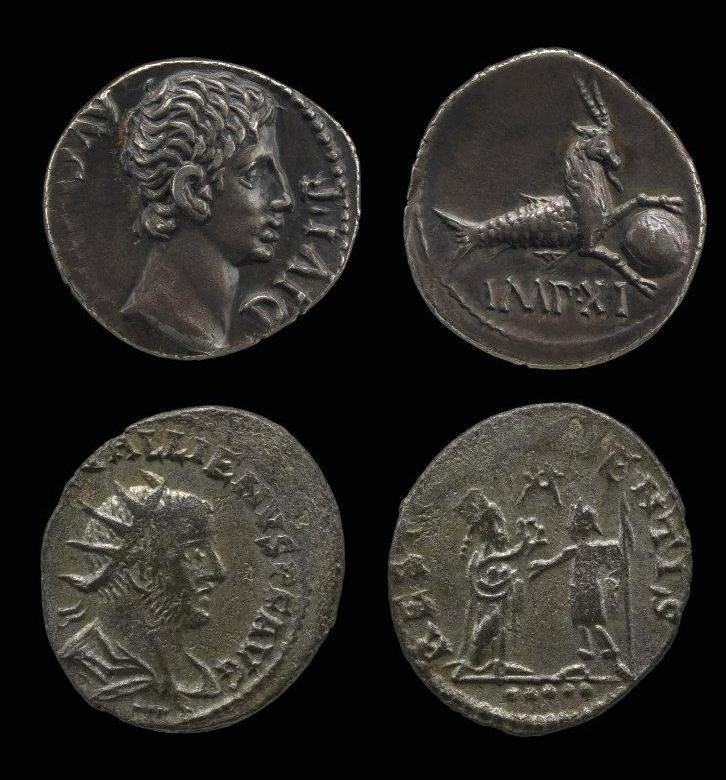

The rise of the Roman Empire ushered in the classicizing Imperial style, ca. 27 BCE - 268 CE. This style was mostly Roman, utilizing the now-standard form of an imperial family member on the OBVERSE. The portraits are more unilateral in style, usually a profile head with an inscription citing the name and most important titles of the featured imperial family member. The composition of these coins stays relatively the same from the time of Augustus to the emperor Gallienus, more than 200 years later. After Gallienus, with the eventual decline of the Roman empire, a more conceptualized Late Antique style takes the forefront.

Notice the similarities between these two coins, one of Augustus and one of Gallienus. Though more than 200 years apart, the composition is quite similar. The minting style, however, makes the difference in age clear. The Augustan coin is more finely cut and naturalistic. The coin of Gallienus is bit more flat, with etched, not modeled details. The difference becomes especially clear when looking at the hairstyle of each emperor. Even with different minting styles, the overall look of these two coins is obviously similar. This may be because it was very common for later emperors to try and connect themselves with Augustus, the most successful and celebrated of all Roman emperors.