Michele Russo

The Pacific Northwest College of Art, or PNCA, has been an essential part of Pacific Northwest art culture for over a century. Originally founded in 1909, it was named the Museum Art School in 1933, and later renamed the Pacific Northwest College of Art in 1981. But not just the school changed the art scene of this region; one of the school’s most influential teachers, Michele Russo (1909-2004) was a vital asset to PNCA and to the Portland art community as a whole.

Born in Connecticut in 1909 but quickly moving to Italy at five years old with his Italian mother and siblings due to the fighting of World War I, Michele Russo did not move back to the United States until 1919; by then, he was a child of two cultures. However, he always had an appreciation for the arts as his mentor in Italy, Giulio Perillo, was a priest and artisan. He attended Yale University in 1934 and earned his MFA in academic and classical art though he preferred artistic experimentation. He painted for the Works Progress Administration before moving to Portland and began teaching at the Museum Art School in 1947 where he taught art and art history until 1974.

Russo changed the culture of PNCA and the Portland art scene throughout his life. In Portland, he advocated for legal protection and professional recognition for artists, helped found the Oregon branch of Artist’s Equity, and the Arlene Schnitzer’s Fountain Gallery (one of the first galleries at the time in 1961), the Portland Center for Visual Arts in 1973, and garnered Portland national and international recognition. In 1977 he was appointed to the Metropolitan Arts Commission, received the Governor's Award for the Arts in 1979, and focused on painting for the rest of his life after retiring in 1974.

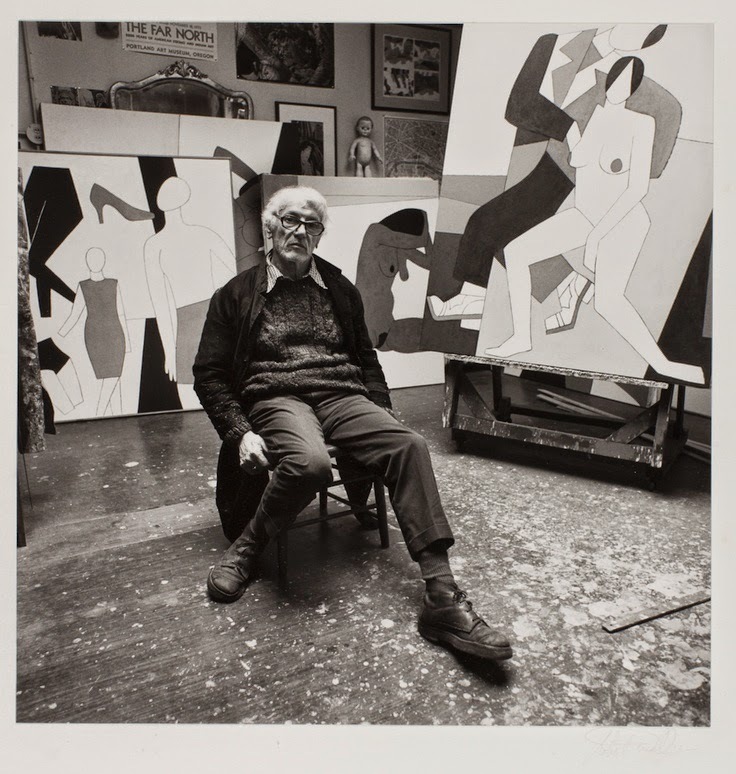

His paintings often explored the theme of the individual. They were figurative, incorporating nude women, sometimes men, heavy black outlines, flat planes of color, a twisted perspective, large canvases, and abstract settings. He flattens and simplifies his works to avoid time and place-specific references. His canvases are intentionally universal and evoke strong emotion- he lets other people insert themselves in the scene and make their own interpretation of nature, society, humans, etc...

In the book The Life and Art of Michele Russo, he is quoted saying, “‘Simple surfaces seemed to be pure and beautiful and emotional, where textured surfaces got to seem very pointless and very trivial and a lot of, I thought, empty display of the skill of the artist’.” This shows the different ways landscape has been interpreted. It is an example of how intertwined abstraction and landscape are in the Pacific Northwest because artists of this region in the 20th century were more than willing to explore new avenues of representation. In landscape, abstraction allows viewers to see how even if we don’t explicitly recognize what is painted as it is not fully representational, we see how land is more than just forms. It is a color, a feeling, an outline. The land is something we are constantly surrounded by and thus is recognizable in ways we may never think of- and that is what abstract landscape shows us.