Illegal Trade

During the Renaissance, the re-invigoration of interest in the ancient world led to an increase of art, philosophy and political ideas that were inspired by the statues and mosaics seen around Rome and Athens and the ideas found in the works of Plato, Aristotle and Cicero - to name just a few.

This work by Raphael, The School of Athens, located in the Raphael Rooms in the Vatican, painted 1509-1511 CE, is an example of this fascination with the ancient world. It features famous figures from Greece and Rome like Plato and Aristotle. It even features some nods to his (relative) contemporaries as Plato is based upon the image of Leonardo da Vinci.

This enthusiasm led to the practice of collecting and even re-producing ancient art: coins, statues, glass and etc. Numismatics, because coins were portable and numerable, became very popular, eventually known as “the King’s hobby.” The increase in demand for ancient artifacts by European nobility led, unavoidably, to the increased production of forgeries made to pass as ancient artifacts, and, just as inevitably, the certain plundering of archaeological sites.

Fast forward a few hundred years and we still find an active following of ancient artifacts: numismatics being one of the most lively and energetic communities. Especially now, forged items and illegally traded artifacts pose, not only a legal responsibility, but an academic and educational torment to modern day collectors and scholars.

Provenance paperwork, or ownership documents dating back to at least 1970, are required by some museums to trade or buy ancient artifacts. Without these documents, it is impossible to know whether something has been illegally smuggled out of its country of origin. Since artifacts have been taken from one country to another for thousands of years, the year of 1970 was agreed upon by the International Council of Museums and the Archeological Institute of America as the year after which no artifacts should be moved out of its country of origin without proper approval, based on the passage of a UNESCO resolution.

This agreement allows museums to keep their acquisitions gathered by earlier collectors – an important step that allows the public to view and learn about ancient artifacts from places that they are not able to visit.

It also, ideally, stops the further plundering of archaeological sites around the world and keeps a particular county’s archaeological and cultural history intact.

This painting by Thomas Cole shows the dilapidated state of the Colosseum in the 1830s. During the Middle Ages, the marble from many ancient monuments, including the Colosseum, was taken to be burned into limestone, an essential ingredient for concrete. The laws surrounding ancient archaeological sites are aimed at stopping this kind of behavior and stopping the further plundering of goods or material found within the site. It is, consequently, illegal to take even a small pebble from the Colosseum today.

With an increased understanding of the importance of cultural heritage and a high value placed on artifacts from the ancient Greek and Roman world, the pains brought about by forgery and illegal trade become increasingly sharp. It can span from native countries losing their ancestral legacy to scholars being cheated of increased understanding of ancient cultures, and thus, a collective loss of knowledge that we have no way of regaining.

Good forgeries can negatively influence the understanding of how coins were used and how common they were. Even worse, the illegal trade of ancient coins erases any contextual evidence of where the coin was found or what it was found with since the provenance documents must be faked. Not only illegal, this practice greatly harms the coin’s academic worth.

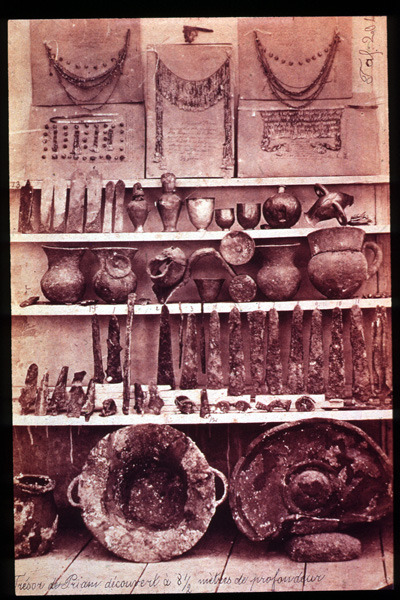

This photo shows the evidence from one of the most infamous smuggling incidents in history. Classical archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann excavated near a town called Chanak in modern-day Turkey. There he discovered several layers of a city that dated back to the Bronze Age (anywhere from 3000 - 1500 BCE). Claiming to have found the famous Trojan city of Troy, he continued fervently with his excavation. In one layer, he found some incredibly well-preserved gold jewelry which he promptly smuggled out of the country, around 1873. Back in Germany, he photographed his wife, Sophia, wearing the ornate headdress and necklace, declaring them the "jewels of Helen." It was only when Sophia wore them out in public that it became apparent to Turkish officials that Schliemann had smuggled them out of the country. Understandably, the Turkish officials were angry and revoked his digging privileges (which were later reinstated after Schliemann traded other gold artifacts to the Ottoman government). Schliemann claimed he was trying to save the artifacts from corrupt local officials, but there is no way to verify his claims.

The story does not end here, however, as the collection of jewels was acquired by the Royal Museums of Berlin in 1881 where it rested until WWII. Around the end of the war in 1945, it disappeared from a protective bunker located under the Berlin Zoo. After almost fifty years of futile searching, the jewels turned up at the Pushkin Museum in Moscow, Russia, where the ownership rights of the jewels are still being debated.

Click on the picture to see both a portrait of Sophia wearing the jewels and Heinrich himself.

Luckily, within the last fifty years, the laws that consider cultural property have been written, largely enforced and have successfully stopped the illegal trade of large shipments of antiquities. Though some effective efforts have been made, there is always a need for vigilant and responsible acquisition as, according to James Hayes, special agent-in-charge with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement and Homeland Security Investigations, the black market in antiquities continues to be the third most profitable black market industry following narcotics and weapons trafficking. Museums, collectors, and scholars are responsible for ensuring their pieces have accurate provenance. Carefully watching out for fakes is also an important part of this process. Our Mithradates II coin is just one small example of how these efforts allow scholars, collectors, and hobbyists to safely and responsibly peruse the rich collection of ancient coins and other antiquities.

Sources for this page:

"Coin collecting." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online Academic Edition. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2013. Web. 30 May. 2013. <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/124774/coin-collecting>.

Choi, Charles Q. "NY Mummy Smugglers Reveal Vast Antiquities Black Market." LiveScience.com. TechMediaNetwork, 26 July 2011. Web. 12 June 2013.

See also:

Anthony Harding. The problem of illicit antiquities: an ethical dilemma for scholars, in History for the Taking. Perspectives on Material Heritage, London: BritishAcademy Policy Centre, 2011, 77-109.

Jason Felch and Ralph Frammolino. Chasing Aphrodite: The Hunt for Looted Antiquities at the World's Richest Museum. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2011.