By Rosie Yanosko, Processing Archivist, ryanosko@willamette.edu

This spring, the Chuck Williams Collection will open for research. Charles Otis “Chuck” Williams was an environmental activist and professional photographer who was of Cascade Chinook descent and a member of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde. His collection, which primarily document his activism, careers, and writings, are held in the Willamette University Archives & Special Collections, while his photographs, which document a plethora of tribal communities, cultural celebrations, and landscapes in the Pacific Northwest, are held in the Oregon Multicultural Archives at the Oregon State University Special Collections & Archives Research Center. This LSTA grant-funded project seeks to preserve and make accessible his papers and photographs.

Born on July 20, 1943, in Portland, Oregon, Williams and his family moved to Petaluma, California several years later. Williams was interested in animals and nature from an early age, and his collection includes a charming childhood scrapbook titled “The Nature Part of the World”. After graduating high school, he took engineering classes at a community college and worked full time as a draftsman/technician, eventually landing a job at Johnson Controls and working on projects for NASA and Boeing. Despite his success, Williams realized he wasn’t cut out for this career path and went on to serve with the Peace Corps in the Dominican Republic and AmeriCorps VISTA in El Paso, Texas. In 1973, he earned a BA in Art from Sonoma State University. Soon after, he began travelling the U.S. extensively, ultimately spending seven years touring the National Parks System (he managed to visit every park in the contiguous U.S.) in his camper van while honing his writing and photography skills. As he travelled, he sent notes to the environmental organization Friends of the Earth (FOE), informing them of issues he noticed while exploring the parks. This caught the attention of FOE’s founder, David Brower, who offered him a position as the organization’s National Parks Representative. While serving in this position, Williams lobbied for stronger protections for national parks and helped establish the Golden Gate and Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Areas. He also wrote articles for FOE’s’s journal, Not Man Apart. His papers from this period contain a manuscript for a book he was writing on the National Parks, as well as research files on the U.S. National Parks Service, and research gathered while writing his article “The Park Rebellion” for Not Man Apart. In the late 1970s, Williams moved back to his native Oregon to take care of his ailing father, and became involved with the fight to preserve the Columbia River Gorge.

In the early 1980s, Williams co-founded the Columbia Gorge Coalition, a grassroots environmental group that started the campaign for the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area. In an article for Earthwatch Oregon in February 1979, Williams summed up the conflict in the Gorge: “Most conservationists agree that strong federal action will be needed to preserve the Gorge. Like Lake Tahoe, the Gorge is shared by two states that seldom see eye to eye, and nearly fifty local jurisdictions spread up and down both sides of the river have never been known to agree on anything. A national scenic area managed by the National Park Service is the most likely proposal.” While Williams and the Coalition wanted the Gorge to be protected from development and managed by the National Park Service, affluent activist groups in Portland favored fewer restrictions on development and thought the land should be managed by the U.S. Forest Service. To help bring attention to the cause, Williams wrote, photographed, and largely self-financed the publication of his book, Bridge of the Gods, Mountains of Fire: A Return to the Columbia River Gorge. After years of contention, the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area Act was passed in 1986. Williams did not think the National Scenic Area (NSA) provided necessary protections and considered the legislation a failure, but continued to fight for stronger protections. He worked with his family to preserve their land allotment in the Columbia Gorge, ultimately establishing the land as the Franz Lake National Wildlife Refuge.

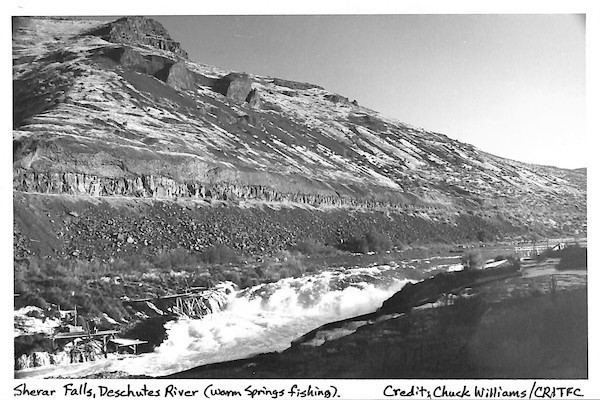

Williams went on to serve as the Public Information Office Manager and Publications Editor for the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fishing Alliance (CRITFC), an organization that coordinates management policy and provides fisheries technical services for the Yakama, Warm Springs, Umatilla, and Nez Perce tribes. Williams’ position at CRITFC led him to begin photographically documenting various tribal and cultural celebrations throughout the Pacific Northwest. In the mid-1990s, he co-founded and managed the Salmon Corps, an AmeriCorps program that worked with Native American youth to restore salmon habitats and riparian areas in Oregon, Washington, and Idaho. After leaving the Salmon Corps, Williams was able to devote more time to his photography and writing. He continued to photograph cultural festivals and celebrations in the Pacific Northwest and exhibited them in the Columbia Gorge Gallery, which he operated out of his home in The Dalles. Proceeds from prints sold were shared with the subjects of his photographs–a testament to the depth of his care for his community. Williams also designed calendars commemorating Celilo Falls and offered slideshows and presentations on the histories of Native American Tribes in the Pacific Northwest. In 2013, Williams, along with David G. Lewis and Eirik Thorsgard, co-authored the chapter “Honoring our Tilixam: Chinookan People of Grand Ronde” in the book Chinookan Peoples of the Lower Columbia.

During his storied career, Chuck Williams was a tireless advocate for the protection of countless rivers, forests, parks, and animals, earning him the nickname “Wild and Scenic Chuck” (in Chinook Wawa, “chuck” means river). He consistently placed environmental causes before his own well being, and this took a toll on his health and finances. In 2015, Williams was diagnosed with lung cancer, and on April 24, 2016 he passed away. Williams was a diligent record keeper and his collection contains a wealth of materials pertaining to grassroots environmental activism, the histories of Native American Tribes in the Pacific Northwest, the U.S. National Parks Service, tribal fisheries, and other subject areas. His collection also provides a crucial counter-narrative to the prevalent discourse surrounding the creation, passage, and effects of the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area Act. Willamette University Archives & Special Collections will open the Chuck Williams Collection for research in the coming months–please stay tuned for updates.