By Doreen Simonsen

Humanities & Fine Arts Librarian, dsimonse@willamette.edu

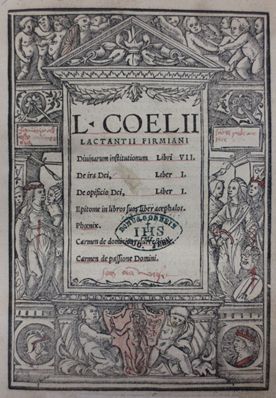

any people have been involved with the creation, printing, illustrating, selling, and purchasing of this particular book over the centuries. The most recent owner this book was Dr. John M. Canse, President of the Kimball School of Theology, a part of Willamette University from 1906 to 1930. The book is called L. Coelii Lactantii Firmiani Diuinarum institutionum libri VII or The Divine Institutes, and the large initial M on the left is one of the illustrations by Hans Holbein the Younger inside this book. “Printed entirely in Latin…it shows the struggle between the ideas of Paganism and those of Christianity… and in 1926, Dr. J. M. Hitt, State Librarian of Washington State considered it to be the oldest book from moveable type found in the Northwest at that time.” 1

Collegian 19303

On June 17, 1953, Dr. Canse gave this book to Willamette University, and inscribed it with the following:

“This author was the silver-tongued Christian of the 4th century. This copy came from a German Monastery to Fort Wayne, Ind. Where I secured it in 1906. Perhaps the oldest book in Moveable type in the Northwest.”2

This silver-tongued Christian was Lactantius, who was born a citizen of the Roman Empire circa 250 C.E. in the northern African town of Cirta, where he taught Latin. Emperor Diocletian summoned him to his court in Nicomedia in Asia Minor (present day Turkey) to teach Latin Rhetoric to administrators of his empire. As a courtier, Lactantius met another follower of the Roman (Pagan) religion, the future emperor Constantine. Both eventually converted to Christianity, and Lactantius fled the region during Emperor Diocletian’s Great Persecution of Christians in 303 C.E.

While in exile, Lactantius wrote this work, The Divine Institutes, “a treatise which sought to commend the truth of Christianity to men of letters and thereby for the first time set out in Latin a systematic account of the Christian attitude to life.”5 “It is the earliest systematic account of Christian morality in Latin.” 6 His written command of the rhetoric of classical texts and “pagan” mythology created a rational argument for Christianity that led him to be called the Christian Cicero. Later he was also called a Christian Humanist and was widely read and published during the Renaissance.

The Dutch philosopher, Erasmus, was one of the many 15th and 16th century Humanistic authors who published an edition of Lactantius’ Divine Institutes. In 1521, the year that our copy of this book was published, Erasmus had settled in Basel, Switzerland, where he befriended the young artist, Hans Holbein the Younger, who painted this famous portrait of him. Erasmus introduced Holbein to his friend, Sir Thomas Moore of England, whose portrait he also painted, and through his connection with Moore, Holbein became the court artist of the Tudors, especially Henry VIII.

by Holbein, 1525 9

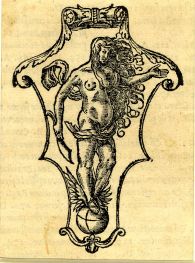

However, while living in Basel, Holbein also created designs for several woodcuts used by printers in that city,8 including Andreas Cratander, who printed our book in 1521. Besides the beautiful title page, Holbein designed Cratander’s Printer’s Mark. An earlier version can be seen on the bottom of the title page of our 1521 book, and the 1525 version is included the images of Printers’ Marks on the ceiling of the West Corridor. Library of Congress Thomas

Jefferson Building.11 “Cratander repeatedly used as his mark the figure of Occasio, or Opportunity. Bald at the back, her hair blown before her, with winged feet she strides the world; in her hand she carries a razor to show how sharply is divided the fleeting present from the irrevocable past.”12

Basel was a major center for Renaissance Humanist and later Protestant publishing during the Reformation. On the title page, Holbein includes putti (cherubs) at the top and the bottom of the page, a classical Italianate frame around the text, and images of women on each side. On the left is Lucretia, a noblewoman of Ancient Rome, who committed suicide by stabbing herself under her breast after being raped by Tarquin, the king’s son. The other woman is Judith, a Israelite widow who beheads Holofernes, an Assyrian general, in order to protect her city. At the bottom are two more putti holding the printer’s mark of Cratander between Roman medaillons in bottom corners. Cratander also used this same title page border later that year for a work by Johannes Oecolampadius, a German Protestant reformer, for whom he continued to publish Protestant works for several years.14

On top of the text of the title page is a stamp from the book’s next known destination, the Jesuit Monastery of Gorheim, in Sigmaringen, Southern Germany, which was in operation from 1852 – 1872. 15

Bookstore, 1888. 16

This may be where the booksellers Simeon & Brother at 714 Calhoun Street in Fort Wayne, Indiana found and purchased our book. They were noted vendors of German and Theology books.17 And they were also listed in the International Adressbuch des Deutschen Buchhandels (Addressbook of German Bookstores) as the only only German bookstore in Fort Wayne, Indiana in 1905.18 This is where Dr. Canse must have found and purchased this book in 1906.

Born in Orland, Indiana in 1869, Dr. Canse graduated with the class of 1899, at DePauw University (a Methodist University) in Greencastle, Indiana, where he later earned his Doctorate in Divinity in 1918. In 1907 he moved from Fort Wayne to the Pacific Northwest, where he served as a minister to several places in Oregon and Washington. He researched the early Methodists in the region and was also active in the Washington State Historical Society. In 1926 he was offered the position of President of Kimball School of Theology by Willamette University’s Board of Trustees, and he held this position until the school closed in 1930. 19 “He gave considerable attention to original research on the Indian Mission Period of Old Oregon. A text entitled, “Missionary Colonizers of the Pacific Northwest,” was written. It appeared first in the Pacific Christian Advocate,”20 a newspaper founded in 1859 in Salem, Oregon by Alvan Waller, one of the founders of Willamette University.

Jason Lee, 1930 21

In 1930 Canse published a biography of Jason Lee called Pilgrim and Pioneer: Dawn in the Northwest. His book includes chapters on “Red Tribes Seek the White Man’s Secret of Success, Indian Camp Meetings and War Clouds, and Indian Missions Fade into White Churches.” In 1932 a reviewer noted that work was “uncritical of Lee…Its chief value, and this is important, is its emphasis upon the religious devotion and zeal that animated Lee’s work.”22

The terror of Diocletian’s Great Persecution of Christians in 303 C.E. forced Lactantius to flee Nicomedia and inspired him to write his arguments in favor of Christianity for educated Latin readers of the 4th century. The printing whirlwind of 16th century Basel produced religious tracts at the beginning of the Reformation, including our book which ended up at a Jesuit monastery in Germany. An American bookseller found it there and added it to his inventory in Indiana, where it fell into the hands of a scholar who celebrated the colonizing of the Northwest by Methodist missionaries. This text has traveled through centuries of religious convictions, conflict, and conversions. If you would like to see this book for yourself, please contact Doreen Simonsen, dsimonse@willamette.edu to make an appointment.

Endnotes:

1. “The Oldest Book of Northwest is Possession of Doctor Canse.” The Willamette Collegian. Vol. VI, No. 7, April 1895, p. 1.

2. Lactantius, Markos Mousouros, Andreas Cratander, and Venantius Honorius Clementianus Fortunatus. L. Coelii Lactantii Firmiani Diuinarum institutionum libri VII … Basileae: apud Andream Cratandrum, 1521. Mark O. Hatfield Library. https://orbiscascade-willamette.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01ALLIANCE_WU/2i92kk/alma9930454435201454

3. “Kimball to Close during 1930-31.” The Willamette Collegian. Vol. XLI, No. 18, February 20, 1930, p. 1.

4. “Fourth-century mural possibly depicting Lactantius (also possibly Apuleius). https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lactantius.jpg

5. Edwards, Mark. “Lactantius.” In The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. : Oxford University Press, 2022. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199642465.001.0001/acref-9780199642465-e-4053.

6. Baldwin, Barry. “Lactantius.” In The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. : Oxford University Press, 1991. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195046526.001.0001/acref-9780195046526-e-2984.

7. Hans Holbein the Younger (German, 1497/8 – 1543), Erasmus, 1523oil on wood, 73.6 × 51.4 cm. The National Gallery, London. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Holbein-erasmus.jpg

8. Schmid, Heinrich Alfred. “Holbeins Thätigkeit für die Baseler Verleger.” Jahrbuch der Königlich Preussischen Kunstsammlungen 20 (1899): 233–62. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25167403.

9. Hans Holbein the Younger (German, 1497/8 – 1543), Printer’s Mark of Andreas Cratander, 1525, Metalcut print on paper, 85 × 59 mm. The British Museum, London. © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

10. Lactantius, Markos Mousouros, Andreas Cratander, and Venantius Honorius Clementianus Fortunatus. L. Coelii Lactantii Firmiani Diuinarum institutionum libri VII … Basileae: apud Andream Cratandrum, 1521.

11. Highsmith, Carol M, Photographer. Second Floor Corridor. Printers’ marks+Columns. Printer’s mark of Cratander in West Corridor. Library of Congress Thomas Jefferson Building, Washington, D.C. , 2007. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2007684459/.

12. Willoughby, Edwin Eliott. “The Cover Design.” The Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy 21, no. 2 (1951): 127–127. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4303991.

13. Hans Holbein the Younger (German, 1497/8 – 1543), Title-Border with Judith and Lucretia, 1521, Metalcut print on paper, 174 × 121 mm. The British Museum, London. © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

14. Colombo, Matteo, Benjamin Manig, and Noemi Schürmann. 2024. “A Reformation in Progress: The Path toward the Reform of Johannes Oecolampadius” Religions 15, no. 9: 1147. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15091147

15. “Kloster Gorheim.” https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kloster_Gorheim

16. “Simeon & Bros. Bookstore.” Souvenir of Fort Wayne, Indiana. 1888, page 12. https://archive.org/details/souveniroffortwa00fort/page/n11/mode/2up

17. “Simeon & Brother.” The Bookmart: A Monthly Magazine of Literary and Library Intelligence, Vol.2, No. 4, September 1, 1884, page 391. https://books.google.com/books?id=Z1ADAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA391&dq=Siemon+%26+Brother.+Booksellers+Wayne&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwi_lp225aL7AhWlCTQIHRQ5AEQQ6AF6BAgDEAI#v=onepage&q&f=false

18. “Fort Wayne (Indiana).” Adressbuch des Deutschen Buchhandels. 1905, V. Abteilung, Seite. 378. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.32044092543537&seq=940&q1=amerika&view=1up

19. John Canse Papers, 1884-1958. Finding Aid. https://wshs-collections.s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/Ms%20148%20Finding%20Aid.pdf

20.“Kimball Policy Yet Uncertain: President Canse Here: Newly Elected Administrator is Well Known Figure in Northwest Circles.” The Willamette Collegian. Vol. XXXiX, No. 1, September 29, 1926, p. 1.

21. Canse, John M. Pilgrim and Pioneer : Dawn in the Northwest. New York ; The Abingdon Press, 1930. https://archive.org/details/pilgrimpioneerda01cans/mode/2up

22. R. C. Clark, Pilgrim and Pioneer: Dawn in the Northwest. By John M. Canse and Jason Lee: Prophet of New Oregon. By Cornelius J. Brosnan, Journal of American History, Volume 19, Issue 3, December 1932, Pages 447–448, https://doi.org/10.2307/1892791